Rereadable: Slaughterhouse-Five

I’ve read Slaughterhouse-Five several times -at least 3.5 times if not once more.

There was a time in the past where I would have nostalgically wondered when I first read it, but thanks to my Amazon purchase history, I can see that I first downloaded it on my Kindle on November 8, 2015 and bought a paperback copy on October 10th, 2019.

There are only a few books and films which I’ve consumed multiple times. The criteria to re-consume are essentially:

The theme/lesson/imagery was captivating enough in the previous round

It’s been long enough that I am fuzzy on the details and will find something new in it when I watch again

The captivating elements?

The (alien species) Tralfamadorian’s concept of time

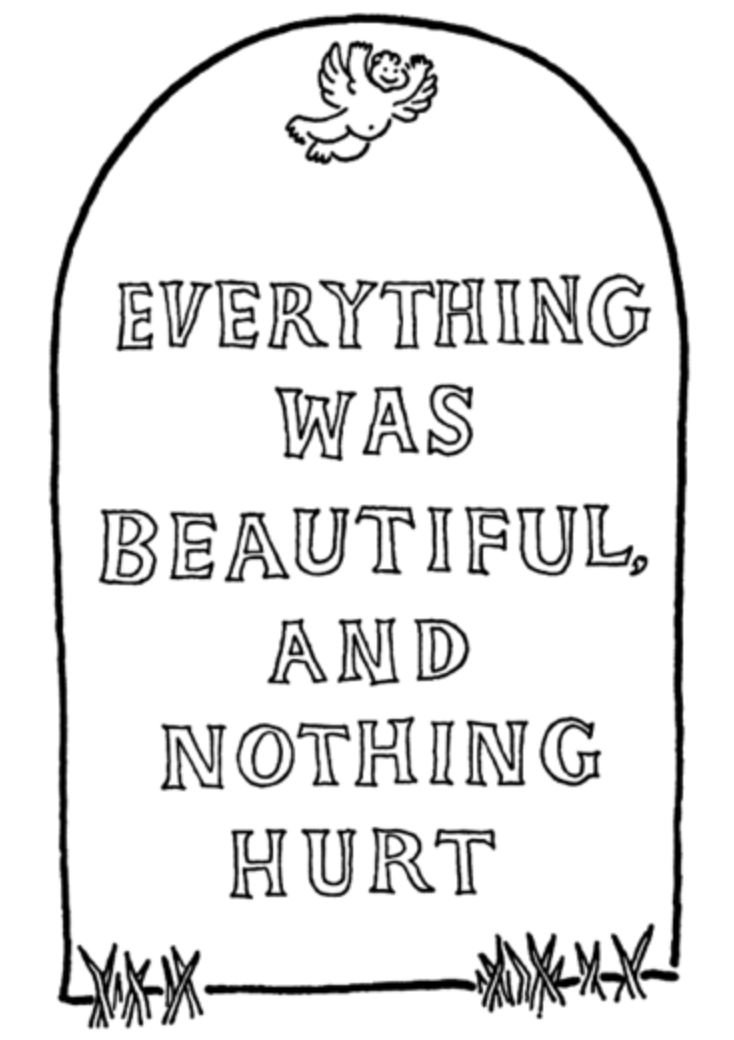

The epitaph Billy’s writes in his head when thinking of the truth of his experience at war

Each of these elements are something I think of often, for whatever reason, probably when contemplating reality.

On Time

Tralfamadorian’s have a completely different understanding of time - “All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance they can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them. It is just an illusion that we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever.”

Whilst Billy is in a Zoo habitat on Tralfalmadore, one of the zoo guides attempt to explain the limited concept of time Earthlings possess.

”The guide invited the crowd to imagine that they were looking across a desert at a mountain range on a day that was twinkling bright and clear. They could look at a peak or a bird or a cloud, at a stone right in front of them, or even down into a canyon behind them. But among them was this poor Earthling, and his head was encased in a steel sphere which he could never take off. There was only one eyehole through which he could look, and welded to that eyehole were six feet of pipe.

This was only the beginning of miseries in the metaphor. He was also strapped to a steel lattice which was bolted to a flatcar on rails, and there was no way he could turn his head or touch the pipe. The far end of the pipe rested on a bi-pid which was also bolted to the flatcar. All Billy could see was the little dot at the end of the pipe. he didn't know he was on a flatcar, didn't even know there was anything peculiar about his situation.

That flatcar sometimes crept, sometimes went extremely fast, often stopped - went uphill, downhill, around curves, along straightaways. Whatever poor Billy saw through the pipe, he had no choice but to say to himself, "That's life. "“

Tralfamadorian’s surfaces the topics of pre-destination and of free will, indicating they have studied many populations and Earthlings are the only one’s who entertain the idea of free will.

“When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. ”

The Epitaph

If I needed to pen something for my headstone in this moment, it would be one of two phrases lyrics from Jimmy Buffett’s He Went to Paris "Some of it’s magic, some of it’s tragic, but I had a good life all the way” or Billy’s epitaph “Everything was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt”, which he thinks only to himself while conversing with him fiancée whilst in the mental institution he has checked himself into not long after returning from war. This has stuck, ever present in my brain, for years.

image from Slaughterhouse-Five

About the book

The book really does cover a lot of ground. It’s alternative title The Children's Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death. There is commentary on the romanticism of war, on religion, mental health, and the perception of life and death themselves.

It’s a semi-autobiographical “anti-war” novel - the account of Kurt Vonnegut’s experience in WW2 as a POW in Germany and survivor of the extensive bombing of Dresden near the end of the war. Main character Billy Pilgrim get’s “unstuck” in time, so the story is told non-linearly, including experiences before, during, and after the war.

Additional Quotes

“And I asked myself about the present: how wide is was, how deep it was, how much was mine to keep.”

“The time would not pass. Somebody was playing with the clocks, and not only the with the electric clocks, but the wind-up kind, too. The second hand on my watch would twitch once, and a year would pass, and then it would twitch again.

There was nothing I could do about it. As an Earthling, I had to believe whatever clocks said - and calendars. ”

“Lot’s wife, of course, was told not to look back [at the brimstone and fire the Lord had rained upon Sodom and Gomorrah] where all those people and their homes had been. But she did look back, and I love her for that, because it was so human.

So she was turned to a pillar of salt. So it goes.

People aren’t supposed to look back. I’m certainly not going to do it anymore.

I’ve finished my war book now. The next one I write is going to be fun.

This one is a failure, and had to be, since it was written by a pillar of salt. ”

“Billy wasn’t a Catholic, even though he grew up with a ghastly crucifix on the wall. His father had no religion. His mother was a substitute organist for several churches in town. She took Billy with her whenever she played, taught him to play a little, too. She said she was going to join a church as soon as she decided which one was right.

She never did decide. She developed a terrific hankering for a crucifix, though. ”

“Derby described the incredible artificial weather that Earthlings sometimes create for other Earthlings when they` don’t want those other Earthlings to inhabit Earth any more. Shells were bursting in the treetops with terrific bangs, he said, showering down knives and needles and razorblades. Little lumps of copper jackets were crisscrossing the woods under the shellbursts, zipping along much faster than sound. ”

“Trout, incidentally, had written a book about a money tree. It has twenty-dollar bills for leaves. It’s flowers were government bonds. Its fruit was diamonds. It attracted human beings who killed each other and made very good fertiliser. ”

I read the book very literally the first time, which looking back feels like a severe misinterpretation. It’s the same feeling of reading Fight Club for the first time and not really being able to pick apart what was real and what was contained within the narrator’s imagination. It’s not quite the same problem I have with deciphering modern religious beliefs and Greek Mythology, but perhaps close enough.

If you believe it, doesn’t that somehow make it true for you?

Have you read Slaughterhouse-Five? What did you think?

P.S. no flights to Tralfamadore currently available.